Yo Lo Vi: An Anniversary of Genocide

“A riot is not a spontaneous act. Genocide does not happen in one night. Hatred does build in one day. It takes time to learn to hate. One has to learn and perform it constantly, like a religion and ritual. It has to be inflicted and tested frequently. Stigmatization and stereotypes have to be performed constantly to achieve a desired end. Branding is an endless temptation. Labeling is a reiterated act. The divide is not a boundary that one marks on the map; the divide becomes only real when it splits the heart.”

(Brahma Prakash, Body on the Barricades, 2023, p.18)

Els afusellaments del 3 de maig (1814). Francisco de Goya, Museo del Prado. https://museupicassobcn.cat/en/whats-on/discover-online/massacre-korea-guernica-cold-war

The 3rd of May marks a year of systemic violence and genocide in Manipur. Despite hollow claims of "timely interventions" and flashy appearances, nothing seems to be changing. Who will save us then?

Going back to the 1800s, it didn't seem like a regular day for Francisco de Goya either. Arguably one of his most famous paintings, commonly known as the “Third of May 1808,” was completed in 1814 and is now housed at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. Critically acclaimed as a seminal work in the history of Western art for its dramatic depiction of the execution of Spanish patriots by French soldiers during the Peninsular War, Goya’s Third of May is a testament to human suffering and resistance which would later inspire works like Pablo Picasso’s Massacre in Korea and Guernica, and Édouard Manet’s series on The Execution of Emperor Maximilian.

In the painting, Goya divides the composition into two main groups, the Spanish on the left and the French on the right. Goya employs various artistic techniques that contribute significantly to its emotional and visual impact. The painting is renowned for its dramatic use of light and shadow, a technique known as chiaroscuro. It starkly contrasts the brightly illuminated victim against the dark backdrop and shadowed French soldiers. This not only focuses the viewer's attention on the central figure but also enhances the thematic contrast between innocence and brutality. The composition further intensifies this effect, with the Spanish victims on one side and the faceless French executioners on the other, emphasizing the dehumanization and mechanical nature of the firing squad.

Symbolically, Goya's work transforms Christian iconography to deepen its commentary on human suffering and injustice. The central figure, with his arms outstretched, mirrors the crucifixion of Christ, positioning him as a martyr for the Spanish resistance. This religious allusion is underscored by the presence of stigmata-like wounds and the use of light around him, suggesting a spiritual and physical struggle. The rough, expressive brushwork and the dark, muted color palette enhance the painting's grim realism and emotional depth. The painting's stark depiction of violence and its emotional depth challenge the viewer to confront the brutal realities of war, making it a powerful anti-war statement that resonates with universal themes of sacrifice and loss.

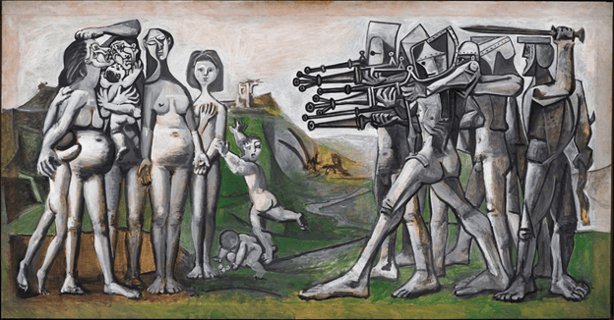

Inspired by Goya’s compositional bifurcation, Pablo Picasso's Massacre in Korea (1951) is an expressionistic painting that serves as a poignant critique of American intervention in the Korean War. The composition juxtaposes two groups: on one side, naked women and children, symbolizing innocence and vulnerability, and on the other, heavily armed "knights," depicted with exaggerated, muscular forms reminiscent of prehistoric giants. These soldiers, also naked but for their misshapen helmets and an assortment of medieval to modern weaponry, are portrayed in a disorganized manner, which Picasso uses to mock the absurdity of war.

Pablo Picasso. Massacre in Korea. Valauri, 18th January 1951. Oil on canvas. 110 x 210 cm. MP203 © Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid 2019. https://museupicassobcn.cat/en/whats-on/discover-online/massacre-korea-guernica-cold-war

Notably, the soldiers are depicted without penises, a symbolic castration that critiques their role as destroyers of life, contrasting starkly with the pregnant state of the women. This representational choice suggests a deeper commentary on the cycle of life and death, with the soldiers' guns serving as a grim substitute for their ability to create life. The painting, by highlighting the tragedy of the Sinchon Massacre and the broader horrors of war, became a controversial masterpiece, criticized for its political message and initially banned in the United States during the Cold War.

But what is the significance of these paintings to us? Some may dismiss the reference to Goya's painting in the Manipur conflict as a mere coincidence. Some may question their relevance or even argue their overuse. The popularity of artworks as archetypes can often trivialize the content they intend to portray. When people are overexposed to a form, it may not evoke the same strong reactions in them as its ubiquity could lessen its initial shock value and intended impact. Repeated encounters can lead to a form of desensitization, making it harder for the audience to engage with it as originally intended.

While satiety may hamper affect, it is based on the assumption that everyone has already seen what artists and art have to offer. It also assumes that people are unchanging and unresponsive to art. The popularity of these paintings, unfortunately, serves as a reminder that genocide is more common than we'd like to admit and there will be more suffering. Art's ubiquity, however, is not solely based on its popularity, but also dependent on how we, as an audience, engage with it. Some have yet to see these artworks, and for some, our experiences have the potential to offer new ways of seeing. As Todd Chavez asks, “Isn’t the point of art less what people put into it, and more what people get out of it?” (Bojack Horseman, s.6, ep.16)

The coincidence of dates between Goya's painting and Manipur's conflict may be notable, but what remains true then and now is the helplessness of the victims and the coldness of the executioners. The women and children depicted in Picasso's painting are not obscure figures, but rather our mothers and siblings brutally persecuted at the hands of cowardly oppressors. As the tyrant tries to erase the memory of suffering and genocide, should we stop creating or sharing art out of fear that it may seem insignificant? If genocide is the result of repeated acts, then shouldn't our efforts to resist such attempts be equally powerful, lest we forget?

Art is a potent form of resistance and in as much as Zo artists have responded with a new-found vigor to our shared experiences, an important caveat here is to ask - What kind of art am I creating? Who is it for? Is it merely a form of leisure, or does it have the potential to inspire action and bring about change? Who am I emancipating? - these questions are not easy to answer, and our struggle is not easy to endure but as a dear friend would say, “The dogs bark, but the Zo caravan goes on.”

Yo Lo Vi, I saw it, I saw the genocide - yes, but what did you do? What will you do?

Note: On the 4th of May 2024 (Saturday), a protest will be organized by the Unau Tribal Women’s Forum and the Joint Unau Delhi Tribal Students Forum at Jantar Mantar, New Delhi from 2 PM onwards. I encourage all readers to join in solidarity if you’re around.

Thangkhankhup Hanghal is a postgraduate student at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Views expressed are personal.

References

Afshar, Pouya. “Iran’s Street Art Shows Defiance, Resistance and Resilience.” The Conversation, 30 Aug. 2023, http://theconversation.com/irans-street-art-shows-defiance-resistance-and-resilience-209678.

Arn, Jackson. “How Goya’s ‘Third of May’ Forever Changed the Way We Look at War.” Artsy, 2 May 2019, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-goyas-third-may-forever-changed-way-war.

Colletti, Francesca. The Power of Memory and Art to Heal a Society After Genocide. https://facingtoday.facinghistory.org/the-power-of-memory-and-art-to-heal-a-society-after-genocide. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

Goya, Francisco. “The Third of May 1808.” World History Encyclopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org/image/17701/the-third-of-may-1808/. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

HØLØDØMØR: Posters Animation. Directed by Yuliya Fedorovych, 2024. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=do2JPMjix2Q.

“Louisiana Channel on Instagram: ‘We Asked the English Conceptual Artist Jeremy Deller If He Thinks Art Has the Power to Change the World. 🌟Watch the Full Interview with Deller via the Link in Our Bio @louisianachannel.’” Instagram, 29 Apr. 2024, https://www.instagram.com/reel/C6VdM3iocKi/.

“Nice While It Lasted.” BoJack Horseman, directed by Aaron Long, 31 Jan. 2020. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt11028176/

Prakash, Brahma. Body on the Barricades: Life, Art and Resistance in Contemporary India. 2023.

Rajvanshi, Khyati. “Behind the Art: Picasso’s ‘Massacre in Korea’: A Powerful Critique of American Involvement in the Korean War.” The Indian Express, 30 Apr. 2023, https://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/art-and-culture/behind-the-art-picassos-massacre-in-korea-a-powerful-critique-of-american-involvement-in-the-korean-war-8575324/

Vartanian, Hrag. My Armenian Genocide Story. https://hragvartanian.com/2008/04/24/my-armenian-genocide-story/comment-page-1/. Accessed Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

Zapella, Christine. Smarthistory – Francisco Goya, The Third of May, 1808. https://smarthistory.org/goya-third-of-may-1808/. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.